INTRODUCTION

Pet obesity is a growing problem. In a cross-sectional study of pets attending five UK veterinary practices (Courcier et al., 2010) it was found that 39% of cats and 59% of dogs were found to be overweight or obese when body condition score was assessed. Owner perception of pets’ bodyweight differs from these findings with the PDSA Animal Welfare Report (2013) stating that just 18% of dog owners reported their dogs as being overweight or obese, and 36% of cat owners choosing a picture of an overweight or obese cat when asked to choose a cat of normal body condition. Obesity is not as clearly defined in animals as it is in humans as the variation in body morphology make a simple BMI calculation impossible, but definitions include the animal being more than 15% over its ideal weight, and the occurrence of fat deposits over the ribcage, spine, base of tail and in the abdomen (Halsberg et al., 2006). For this case, a 9-point body condition scoring chart was used (Royal Canin, 2014) as well as recording body weight and taking neck, chest and waist measurements.

Obesity is not just a matter of appearance; obesity is identified as a risk factor for many common canine diseases including osteoarthritis, cardiorespiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, some cancers, dermatological problems, and increased risk to animals under anaesthesia (German, 2006). It has also been shown that longevity is affected by body condition when factors other than food intake are equal. A group of Labrador Retrievers with a mean BCS of 4.5/9 lived an average of 1.8 years longer than the group with a mean BCS of 6.8/9 (Lawler et.al. 2005). Both groups suffered from similar illnesses and causes of death, but the overweight group was affected earlier in life.

Many veterinary practices run weight loss clinics, but my own experience has been that client compliance is poor and that even when pets lose weight, many regain it after reaching target weight. Adding owner education into the weight loss programme doesn’t significantly alter weight loss (Yaissle et al., 2004) and up to half of dogs achieving weight loss will put weight back on (German et al., 2012). A behavioural approach as part of a weight loss plan has previously been described (Halsberg et al., 2006). This case expands on the use of behavioural treatment by using EMRA evaluation and follows an obese dog and her owners during a weight loss programme incorporating a weight loss diet and behaviour management techniques.

THE SUBJECT

Goldie is a Golden Retriever and was 3 years old at the time of presentation. She was neutered at 6 months old prior to her first season. She was diagnosed with bilateral cataracts in August 2014 and required surgery, but this has been delayed until she reaches a normal body weight. As part of the investigation of her cataracts diabetes was ruled out. At the start of her weight loss programme Goldie weighed 41.5kg, the normal bodyweight for a female Golden retriever is 25-32kg with show types like Goldie being at the higher end (Dog Breed Information, 2015). If Goldie’s ideal body weight is 32kg she was nearly 30% over ideal and with a Body Condition Score of 8/9 at the start of treatment. The ophthalmologist suggested a target weight of 35kg before surgery could be considered due to the higher anaesthetic risk for obese dogs.

Goldie’s weight, heart rate, respiratory rate, body-condition score, neck, chest and waist measurements were initially measured every week at Companion Care Vets in Eastbourne. The frequency was reduced to every two weeks as this was more convenient for her owners. Goldie was seen at the same time of day each week and readings taken after she has had time to settle in the consulting room. The examination was made by the same person each time to reduce any variability in observations by different people (Zachary et al., 2001) and because Goldie may have reacted differently to other members of staff altering her heart and respiratory rates.

HISTORY AND INITIAL ASSESSMENT

For the owners’ convenience, assessments were made at the veterinary practice and relied on observations of Goldie in the clinic environment and discussion about her lifestyle. I was able to observe her entering the practice which is situated at the back of a pet store. Goldie walked in on a loose lead with her head held level and her tail gently wagging. She did not seem overly interested in the other dogs and people in the store or the waiting room, or in the toys, food and small pets on display.

Goldie was previously fed a combination of dry food and canned wet food. Goldie’s owners describe her as not being that interested in food and often leaving some. She has traditionally been fed half a can of wet food with ad-lib dry food available all day as well as dog biscuits, chews and human food at mealtimes. The practice had recommended 374g per day of Veterinary Weight Management Dry food for Goldie which had been calculated to give between 1 and 3% weight loss each week and to take up to 12 weeks to reach her target of 35kg. Goldie’s owners had found it hard to change Goldie onto the new food and had resorted to handfeeding and adding cooked vegetables.

Goldie’s clinical history suggests weight control has been an issue since puppyhood with numerous notes on her record that her food intake and weight gain should be monitored. Goldie weighed 32.1kg at her Annual Health Check in June 2012 (aged 2 years) but had ballooned to 42.5kg by June 2013. After advice from the vet, Goldie’s owners did manage to get her to lose almost 2 kg, but this was soon put back on. Goldie’s owners felt her weight had become a major problem over the last year as, due to their own mobility problems, Goldie had been receiving minimal outdoor exercise. To compensate for a lack of walks Goldie’s owners (her female owner in particular) have given her treats and chews including dog biscuits, rawhide chews and dental sticks. If Goldie was present during the family mealtimes she would beg at the table and be fed. In an attempt to stop the begging, Goldie is now shut away from the owners at mealtimes. Over the last year Goldie has been having one or two short walks a day as her male owner has hip problems and her female owner had knee surgery. Now the female owner is more mobile she is trying to take Goldie for two or three 40-minute walks a day. She is on lead until they get to the beach, then off lead. Goldie enjoys off-lead walks in the field behind the owners’ house but is not allowed to do this at the moment as she rolls in cowpats. Goldie ‘plods along’ in her owners’ words on beach walks and isn’t interested in chasing or retrieving balls. She does like to sniff on beach walks. Goldie is groomed about once a week. Goldie doesn’t chew toys but will chew rawhide and dental chews.

Emotional Assessment

1) Dog food

2) Food treats

Goldie is not showing any extremes of emotion during her day and appears to get very little pleasure out of activities including eating dog food. She appears to gain more pleasure from higher value foods such as table scraps and chew toys and will beg for these.

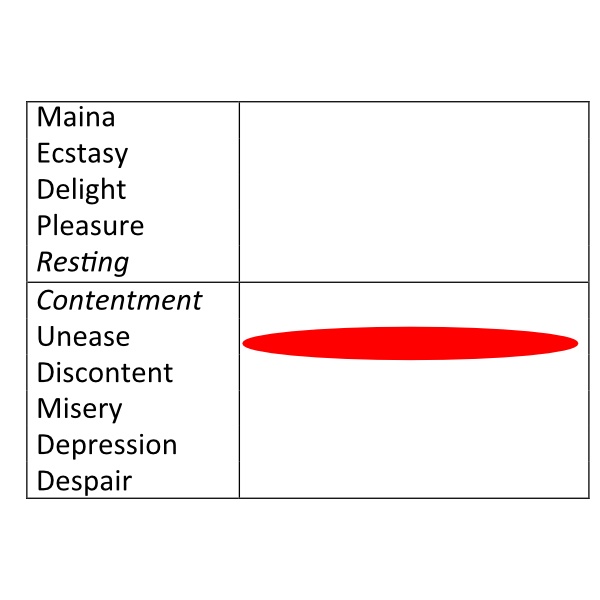

Mood State Assessment

At first glance Goldie appears to spend her entire life in ‘resting contentment’, but her lack of interest in the stimulating environment of the pet store and veterinary practice made me concerned that her background mood is actually somewhat low and that she is simply resigned to an under-stimulated life.

Hedonic Budget

Goldie’s life is very empty for a young dog from a working breed. Although Goldie is from show/pet parents, rather than working gundog parents, I would expect her to want to be more active in hunting and retrieving games. Goldie is getting sufficient chewing, and this is one of the few activities she seems to really enjoy, but at the moment she is being given edible chews which are increasing the calories she takes in. Goldie spends much of the day lying in her bed and her owners perceive that when she comes up to them in the house she is asking for treats, when she may just be trying to initiate social contact.

Reinforcement Assessment

Goldie’s owners see her as a laid back, content dog. They have been happy to leave her resting in her bed and have not encouraged play, hunting or retrieving games on walks as Goldie appears content just walking beside them. Goldie’s owners have fed her treats or table scraps when she has tried to initiate social contact. In a normal dog a feeling of hunger would engage the SEEKING system and finding and eating food would both lead to a feeling of fullness and a feeling of pleasure from release of dopamine in the brain (Panksepp, 1998). Goldie may be ‘asking’ for food treats whenever she feels discontent rather than engaging in play or other activities that could stimulate dopamine release. Feeding Goldie not only has the effect of temporarily making her feel better, but also enhances her owner’s feeling of wellbeing, probably through stimulation of the CARE system (Panksepp, 1998) so feeding Goldie when she ‘asks’ for treats is rewarding both for Goldie and her owners. Shutting Goldie away when her owners eat has physically stopped her begging, but it could lower her mood state further by making her feel isolated. Isolation can trigger the PANIC circuits in the brain leading to feelings of distress (Panksepp, 1998).

Plan

Try and find a toy Goldie will play with on walks. Use this for tug, fetch or hunting games. Replace giving treats with alternative interaction such as playing with a toy, grooming or giving a puzzle feeder. Feed two meals a day of 1/3 of the kibble each and reserve 1/3 of the kibble for use in chew feeders, puzzle feeders or for ‘treats’. Feed Goldie at human mealtimes to reduce the risk of begging without making Goldie feel isolated.

DIET

Goldie’s diet as an adult dog had been half a can of wet food with ad lib dry kibble. The wet food was providing a fairly high protein (40% dry matter-DM), high fat (31% DM) diet, but was balanced out to some extent by the dry kibble (24% protein and 11% fat DM). The wet food is not a complete food and is designed to be fed with a mixer to provide carbohydrates (72% carbohydrate DM). The dry kibble is a complete food rather than a mixer and though it is made of higher quality protein sources it will provide more calories than a mixer. A high-fat diet can reduce the transport of insulin into the brain and the insulin sensitivity of peripheral tissues and predisposes to weight gain (Blanchard et al., 2004).

Recently, Goldie’s diet has been changed to a different brand of canned and dry on the suggestion of friends. Both the canned and dried versions are quite low in fat (10% and 7% DM respectively) and moderate in protein (both 21% DM) but high in carbohydrates (64% and 63% DM).

Because the owner’s previous attempts to reduce Goldie’s weight had failed, and because of the urgency for her to lose weight in order to have her cataract surgery it was decided to switch Goldie to a specially designed veterinary weight management diet. This diet provides a relatively high proportion of protein (33% DM) with a restricted calorie content. This type of diet was found to be effective in promoting rapid weight loss in dogs while maintaining muscle mass (Blanchard et al. 2004). In addition, this diet is high in fibre (18.3% DM) compared to the diets Goldie was previously fed (all around 3% DM fibre). A high-fibre content contributes to a feeling of fullness (satiety) after a meal, reduced begging, and improved weight loss (Weber et al. 2007). Satiety Control also includes the amino acid L-Carnitine which helps maintain or increase lean mass and decrease fat mass during weight loss (Heo et al., 2000) and supplies the required levels of vitamins and minerals for health.

The Veterinary Nurse contacted the veterinary pet food supplier to determine how much Goldie should be fed each day and between 333g and 374g was suggested. She also advised the owners to split this into two or three meals. I suggested the feeding times should coincide with human mealtimes to reduce begging without Goldie feeling isolated. Ad-lib feeding, which Goldie was previously used to, is associated with dogs becoming overweight (Lawler et al. 2005).

HEALTH

Medical conditions can affect a dog’s ability to maintain normal weight as well as being influenced by a dog being overweight. When Goldie’s cataract was first noted a urine dipstick test was done to rule out diabetes which is more common in overweight dogs. The test was negative, and Goldie’s cataract was found to be of an inherited type when assessed by the ophthalmologist.

Thyroxine plays a major role in controlling metabolic rate in dogs (Aspinall and Cappello 2009) and hypothyroidism is a condition from which Golden Retrievers are at higher risk than other breeds (Milne and Hayes 1981). Physical examination made hypothyroidism an unlikely diagnosis as, although Goldie was overweight and rather lethargic, her heart and respiratory rates were normal. Blood tests to check the thyroid level could be considered if Goldie did not lose weight as expected.

RESULTS

Week 2

- Goldie had lost both weight and on measuring this week

- Goldie’s owners reported she was enjoying the new chew/feeding toys.

- Goldie is not eating her full allowance of food but is eating around 312g/day with no extras or treats.

- Goldie’s owners are struggling to get her to engage in play with toys on her walks, but they have been playing a ‘run away’ game which she seems to enjoy (and which the female owner says is good for her fitness too!).

EMRA Assessment

There is little change in Goldie’s EMRA assessment this week. It is good to see that she is gaining as much enjoyment from the new chew/feeding toys as she was from the high calorie chews. Providing these toys at human mealtimes is preventing Goldie becoming frustrated and begging for food. Assessing her mood state remains difficult, but I still feel it is suboptimal as her interactions with her environment are so low key.

Week 3

- There was no change in Goldie’s weight or measurements this week. She enjoys chasing toys but will not retrieve which limits their use on walks. Goldie enjoys running into the sea after thrown stones.

- The biggest change was in Goldie’s general demeanour. She walked into the store with her head up and tail wagging gently. Goldie’s owners said she was keener to go for walks and more interested in interacting with other dogs.

Mood State

Weeks 5-9

Goldie and her owners are now settled into their new routines and Goldie appears to get as much pleasure from simple social contact or grooming from her owners as she previously did from her owners supplying food treats. Touch is an important part of social bonding both between species as well as within a species. Opiates are known to be released in response to touch and both prolactin and oxytocin are thought to be important in the comfort derived from contact (Panksepp, 1998). Goldie’s weight loss continues well and by week 9 her BCS is 7/9.

Weeks 9-15

Weight loss continues, and Goldie’s mood state continues to be good. Goldie’s owners did suffer health problems during this period and couldn’t walk her as much but continued to find games to play indoors such as hide and seek which have kept Goldie happy and reduced her begging for food. By week 15 BCS is 6/9.

Weight loss chart

Measurements

Heart and respiratory rate were recorded at each assessment but did not vary during the course of Goldie’s weight loss. Heart rate was consistently around 100 in the clinic and she was always panting gently.

Photographs

Because Goldie has a profuse coat the Before and After images are not as striking as they might have been in a smooth coated dog.

Week 1

Week 7

Week 15

Monitoring for this study stopped at week 15 but Goldie has continued to visit the practice for monthly weigh-ins. Her weight at the end of May was 34.4kg and her BCS 5/9. Her owners are aiming for an eventual ideal weight of 32kg.

DISCUSSION

Obesity in pets is an increasing problem (Courcier, 2010) and is a contributing factor in many common canine diseases (German, 2006). Although weight gain can be a symptom of diseases such as hypothyroidsism, or a side effect of medication such as corticosteroids (Ahrens, 1996) the most common cause is simply more calories being consumed than are expended (German, 2006). Many factors affect the likelihood of a dog developing obesity including the energy density of the foods available, the amount of exercise done, and genetic factors.

A number of breeds are over represented in the population of overweight dogs seen at vet’s clinics suggesting a dog’s breed or type can have an influence on its tendency to gain weight. Overrepresented breeds include; Labrador Retriever, Cairn Terrier, Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Scottish Terrier, and Cocker Spaniel (Edney and Smith, 1986). Research in humans suggests that numerous small genetic variations can add up to an increased risk of obesity (Day and Loos, 2001). In dogs it is thought that selective breeding may mean certain breeds have a small number of very influential genetic mutations that affect a breed’s propensity to gain weight (Raffan, 2013). Leptin is a hormone produced by adipose cells which acts on the hypothalamus to regulate food intake, however mutations in the leptin gene and its receptors in rats can predispose to obesity (Jeffrey and Jeffrey 1998). Human research has shown that gene variations affect weight gain by altering the mechanisms that link energy expenditure to food seeking behaviours, and reducing the satiety that eating should bring (Raffan, 2013). If the same breakdown in the link between energy intake and output and the same increased drive to seek out food, but be less satisfied by it exists in dogs then it shouldn’t be surprising that some dogs struggle to lose weight. One way in which a behavioural approach can help is through the use of puzzle feeders or scatter feeding to allow the dog to engage in food seeking behaviour for a larger proportion of the day, whilst ingesting fewer calories.

There are currently no weight loss drugs marketed for dogs in the UK, however two drugs were launched onto the veterinary market in 2007; dirlotapide (Slentrol: Zoetis) and mitratipide (Yarvitan: Janssen Animal Health). Both drugs are microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) inhibitors which reduce the absorption of fat from the intestines. Dirlotapide was also shown to reduce appetite in dogs, and this was believed to be due to increased secretion of peptide YY (Wren et. al, 2007). Ingesting fatty foods suppresses hunger through free fatty acids which stimulate gut peptides, including peptide YY to be released from cells in the intestinal epithelium (Hata et.al., 2011). Injecting peptide YY had been shown to reduce food intake in rats (Batterman et.al. 2002). Both drugs were contraindicated for dogs with impaired liver function, as well as growing, pregnant or lactating dogs and both have now been removed from the market.

Neutering is often cited as a factor in pet obesity (German 2006) A lower metabolic rate in neutered animals is suggested as the main cause in some studies (Flynn et. al. 1996) however this study also showed a change in the appetite of neutered cats. Another study in cats showed that neutered cats had higher circulating levels of leptin, which correlated with higher body fat, and lower energy expenditure in neutered cats (Martin et.al. 2001) . It is not clear why high circulating leptin in neutered cats does not suppress appetite however the control of appetite is complex and oestrodiol has been found to have an effect on numerous feedback controls (Asarian and Geary 2006). Although the exact mechanisms by which neutering predisposes dogs and cats to weight gain are not clear careful management of pets post neutering is recommended to prevent obesity.

Resting heart and respiratory rates are usually higher in overweight animals however no change was seen in Goldie’s heart or respiratory rates during her weight loss. This may be because readings were taken in the clinic, an environment in which Goldie may be expected to me more aroused (Bragg et. al. 2015). Measuring the heart and respiratory rates at home, especially if done by the owners rather than a stranger may have given different results.

Dieting can be difficult in both humans and animals as the need to eat is a primary one and food cannot be avoided as cigarettes can be for a human, or balls for a ball obsessed dog. Where the background mood state of an animal is low it may engage the SEEKING system (Panksepp 1998) in pursuit of food to raise dopamine levels even without the trigger of hunger leading to overeating. By looking for other ways to stimulate the SEEKING system, such as hunting for toys mood state can be improved and begging or food stealing behaviours reduced. With companion animals the situation is complicated by feeding the pet making the owner feel good. A behavioural approach which also considers the owner’s feeling and needs seems more likely to succeed. This might include suggesting grooming or play with the dog as an alternative to feeding as this social contact can raise opiate and oxytocin levels in both the human and dog leading to a feeling of wellbeing (Panksepp 1998).

CONCLUSION

Goldie’s case shows that including an EMRA behavioural assessment into a weight loss programme for dogs can highlight causes and reinforcers of obesity, and increase the likelihood of successful weight loss. Goldie’s owners had previously tried, and failed to control her weight. A big turning point seemed to be the realisation that Goldie’s apparently laid back, content demeanour may in fact be a display of resignation to a rather boring life. Improving the hedonic budget and mood state by adding activities relevant to the dog’s age and breed can reduce reliance on food to increase mood and also provides owners with alternative ways to interact with and reward their dog. Seeing the change in her attitude and willingness to engage in activities proved as rewarding to Goldie’s owners as seeing her weight decrease. However there is no doubt that the goal of reducing Goldie’s weight so she could have surgery to improve her vision was also a very motivating factor.

REFERENCES

Ahrens, F.A. (1996) NVMS: Pharmacology. Williams and Wilkins, Maryland, USA.

Asarian, L. Geary, N. (2006) Modulation of appetite by gonadal steroid hormones. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Volume: 361 Issue: 1471

Aspinall, V. Cappello, M. (2009) Introduction to Veterinary Anatomy and Physiology Textbook (2nd Edition)Butterworth Heinemann Elsevier

Batterham, R.L. Cowley, M.A. Small, C.J. Herzog, H. Cohen, M.A. Dakin, C.L. Wren, A.M. Brynes, A.E. Low, M.J. Ghatei, M.A. et al. (2002) Gut hormone PYY(3-36) physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature 418:650–654

Blanchard, G. Nguyen, P. Gayet, C. Leriche, I. Siliart, B. Paragon, B-M. (2004) Rapid Weight Loss with a High-Protein Low-Energy Diet Allows the Recovery of Ideal Body Composition and Insulin Sensitivity in Obese Dogs. The Journal of Nutrition, vol.134 no.8 2148S-2150S

Bragg, R.F. Bennett, J.S. Cummings, A. Quimby, J.M. (2015) Evaluation of the effects of hospital visit stress on physiologic variables in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, Vol. 246, No. 2, Pages 212-215

Courcier, E. A., Thomson, R. M., Mellor, D. J. and Yam, P. S. (2010), An epidemiological study of environmental factors associated with canine obesity. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 51: 362–367

Day, F.R. and Loos, R.J.F. (2011)Developments in Obesity Genetics in the Era of Genome-Wide Association Studies. Journal of Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics 2011;4:222–238

Dog Breed Information (2015)Golden Retriever [on-line] Available at http://www.dogbreedinfo.com/goldenretriever.htm [Accessed 11/2/15]

Edney, A.T. and Smith, P.M. (1986) Study of obesity in dogs visiting veterinary practices in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec. 118:391–6.

Flynn, M.F. Hardie, E.M. Armstrong, P.J. (1996) Effect of ovariohysterectomy on maintenance energy requirements in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc.;209:1572–81

German, A.J. (2006) The growing problem of obesity in dogs and cats. Journal of Nutrition, vol. 136 no. 7 1940S-1946S

German, A.J. Holden, S.L. Morris, P.J. Biourge, V. (2012) Long-term follow-up after weight management in obese dogs: the role of diet in preventing regain. The Veterinary Journal. Volume 192, Issue 1, Pages 65–70

Halsberg, C. Heath, S. Iraka, J. Muller, G. (2006) A behavioural approach to canine obesity. Waltham Focus Special Edition

Hata, T. Mera, Y. Ishii, Y. Tadaki, I. Tomimoto, D. Kuroki, Y. Kawai, T. Ohta, T. and Kakutani, M. JTT-130, a Novel Intestine-Specific Inhibitor of Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein, Suppresses Food Intake and Gastric Emptying with the Elevation of Plasma Peptide YY and Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 in a Dietary Fat-Dependent Manner. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Theraputics; vol. 336 no. 3 850-856

Heo K, Odle J, Han IK, Cho W, Seo S, van Heugten E, Pilkington DH. (2000). DietaryL-carnitine improves nitrogen utilization in growing pigs fed low-energy, fat-containing diets. Journal of Nutrition ;130:1809–14

Jeffrey, M. F. Jeffrey, L. H. (1998) Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature 395, 763-770

Kaiyala, K.J. Prigeon, R.L. Woods, S.C. Schwartz, M.W. (2000) Obesity induced by a high-fat diet is associated with reduced brain insulin transport in dogs. Diabetes. Vol. 49. No. 9 1525-1533

Lawler DF, Evans RH, Larson BT, Spitznagel EL, Ellersieck MR, Kealy RD. (2005). Influence of lifetime food restriction on causes, time, and predictors of death in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. ;226:225–31

Martin, L. , Siliart, B. , Dumon, H. , Backus, R. , Biourge, V. and Nguyen, P. (2001), Leptin, body fat content and energy expenditure in intact and gonadectomized adult cats: a preliminary study. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 85: 195–199

Milne, K.L. Hayes, H.M. (1981) Epidemiologic feature of canine hypothyroidism. The Cornell Veterinarian. 71 (1): 3-14

Panksepp, J. (1998) Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. Oxford University Press.

PDSA Animal Welfare Report (2013) [on-line] Available at https://www.pdsa.org.uk/files/Paw_Report_2013.pdf Accessed 15/10/14 [Accessed 12/10/14]

Pets at Home (2015) Dog Food and Dog Treats [on-line] Available at http://www.petsathome.com/shop/en/pets/dog/dog-food-and-treats [Accessed 11/2/15]

Raffan, E. (2013) The big problem: battling companion animal obesity. Veterinary Record, 173: 287-291

Royal Canin (2014) Body Condition Score Chart- Large dog [On-line] Available at https://petslimmer.co.za/articles-and-latest-news/how-to-tell-if-you-have-an-overweight-dog [Accessed 10/2/15]

Weber, M., Bissot, T., Servet, E., Sergheraert, R., Biourge, V. and German, A. J. (2007), A High-Protein, High-Fiber Diet Designed for Weight Loss Improves Satiety in Dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 21: 1203–1208.

Wren, J.A. Gossellin, J. and Sunderland, S.J. (2007) Dirlotapide: a review of its properties and role in the management of obesity in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Volume 30, Issue Supplement s1, pages 11–16.

Yaissle, J.E. Holloway, C. Buffington, T. (2004) Evaluation of owner education as a component of obesity treatment programs for dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. Jun 15;224(12):1932-5

Zachary V. et al. (2001) The reliability of vital sign measurements. Annals of Emergency Medicine , Volume 39 , Issue 3 , 233 – 237